Jump to: navigation, search

Heart failure

Classification and external resources |

| |

Heart failure (HF) is a condition in which a problem with the structure or function of the heart impairs its ability to supply sufficient blood flow to meet the body's needs.[1] It should not be confused with cardiac arrest (see Terminology, below).

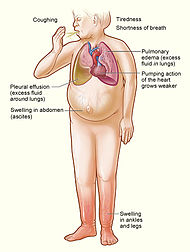

Common causes of heart failure include myocardial infarction and other forms of ischemic heart disease, hypertension, valvular heart disease and cardiomyopathy.[2] Heart failure can cause a large variety of symptoms such as shortness of breath (typically worse when lying flat, which is called orthopnea), coughing, ankle swelling and reduced exercise capacity. Heart failure is often undiagnosed due to a lack of a universally agreed definition and challenges in definitive diagnosis. Treatment commonly consist of lifestyle measures (such as decreased salt intake) and medications, and sometimes devices or even surgery.

Heart failure is a common, costly, disabling and deadly condition.[2] In developing countries, around 2% of adults suffer from heart failure, but in those over the age of 65, this increases to 6—10%.[2][3] Mostly due to costs of hospitalisation, it is associated with a high health expenditure; costs have been estimated to amount to 2% of the total budget of the National Health Service in the United Kingdom, and more than $35 billion in the United States.[4][5] Heart failure is associated with significantly reduced physical and mental health, resulting in a markedly decreased quality of life.[6][7] With the exception of heart failure caused by reversible conditions, the condition usually worsens over time. Although some patients survive many years, progressive disease is associated with an overall annual mortality rate of 10%.[8]

Terminology

Heart failure is a global term for the physiological state in which cardiac output is insufficient for the body's needs.

This may occur when the cardiac output is low (often termed "congestive heart failure").[9]

In contrast, it may also occur when the body's requirements for oxygen and nutrients are increased, and demand outstrips what the heart can provide, (termed "high output cardiac failure") [10]. This can occur in the context of severe anemia, Gram negative septicaemia, beriberi (vitamin B1/thiamine deficiency), thyrotoxicosis, Paget's disease, arteriovenous fistulae or arteriovenous malformations.

Fluid overload is a common problem for people with heart failure, but is not synonymous with it. Patients with treated heart failure will often be euvolaemic (a term for normal fluid status), or more rarely, dehydrated.

Doctors use the words "acute" to mean of rapid onset, and "chronic" of long duration. Chronic heart failure is therefore a long term situation, usually with stable treated symptomatology.

Acute decompensated heart failure, which should just describe sudden onset HF, is also used to describe exacerbated or decompensated heart failure, referring to episodes in which a patient with known chronic heart failure abruptly develops symptoms.[citation needed]

There are several terms which are closely related to heart failure, and may be the cause of heart failure, but should not be confused with it:

- Cardiac arrest, and asystole both refer to situations in which there is no cardiac output at all. Without urgent treatment, these result in sudden death.

- Heart attack refers to a blockage in a coronary (heart) artery resulting in heart muscle damage.

- Cardiomyopathy refers specifically to problems within the heart muscle, and these problems usually result in heart failure. Ischemic cardiomyopathy implies that the cause of muscle damage is coronary artery disease. Dilated cardiomyopathy implies that the muscle damage has resulted in enlargement of the heart. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy involves enlargement and thickening of the heart muscle.

[edit] Classification

There are many different ways to categorize heart failure, including:

- the side of the heart involved, (left heart failure versus right heart failure)

- whether the abnormality is due to contraction or relaxation of the heart (systolic dysfunction vs. diastolic dysfunction)

- whether the problem is primarily increased venous back pressure (behind) the heart, or failure to supply adequate arterial perfusion (in front of) the heart (backward vs. forward failure)

- whether the abnormality is due to low cardiac output with high systemic vascular resistance or high cardiac output with low vascular resistance (low-output heart failure vs. high-output heart failure)

- the degree of functional impairment conferred by the abnormality (as in the NYHA functional classification)

Functional classification generally relies on the New York Heart Association Functional Classification.[11] The classes (I-IV) are:

- Class I: no limitation is experienced in any activities; there are no symptoms from ordinary activities.

- Class II: slight, mild limitation of activity; the patient is comfortable at rest or with mild exertion.

- Class III: marked limitation of any activity; the patient is comfortable only at rest.

- Class IV: any physical activity brings on discomfort and symptoms occur at rest.

This score documents severity of symptoms, and can be used to assess response to treatment. While its use is widespread, the NYHA score is not very reproducible and doesn't reliably predict the walking distance or exercise tolerance on formal testing.[12]

In its 2001 guidelines, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association working group introduced four stages of heart failure:[13]

- Stage A: Patients at high risk for developing HF in the future but no functional or structural heart disorder;

- Stage B: a structural heart disorder but no symptoms at any stage;

- Stage C: previous or current symptoms of heart failure in the context of an underlying structural heart problem, but managed with medical treatment;

- Stage D: advanced disease requiring hospital-based support, a heart transplant or palliative care.

The ACC staging system is useful in that Stage A encompasses "pre-heart failure" - a stage where intervention with treatment can presumably prevent progression to overt symptoms. ACC stage A does not have a corresponding NYHA class. ACC Stage B would correspond to NYHA Class I. ACC Stage C corresponds to NYHA Class II and III, while ACC Stage D overlaps with NYHA Class IV.

[edit] Diagnostic criteria

No system of diagnostic criteria has been agreed as the gold standard for heart failure. Commonly used systems are the "Framingham criteria"[14] (derived from the Framingham Heart Study), the "Boston criteria",[15] the "Duke criteria",[16] and (in the setting of acute myocardial infarction) the "Killip class".[17]

[edit] Signs and symptoms

[edit] Symptoms

Heart failure symptoms are traditionally and somewhat arbitrarily divided into "left" and "right" sided, recognizing that the left and right ventricles of the heart supply different portions of the circulation. However, heart failure is not exclusively backward failure (in the part of the circulation which drains to the ventricle).

There are several other exceptions to a simple left-right division of heart failure symptoms. Left sided forward failure overlaps with right sided backward failure. Additionally, the most common cause of right-sided heart failure is left-sided heart failure. The result is that patients commonly present with both sets of signs and symptoms.

[edit] Left-sided failure

Backward failure of the left ventricle causes congestion of the pulmonary vasculature, and so the symptoms are predominantly respiratory in nature. The patient will have dyspnea (shortness of breath) on exertion (dyspnée d'effort) and in severe cases, dyspnea at rest. Increasing breathlessness on lying flat, called orthopnea, occurs. It is often measured in the number of pillows required to lie comfortably, and in severe cases, the patient may resort to sleeping while sitting up. Another symptom of heart failure is paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, a sudden nighttime attack of severe breathlessness, usually several hours after going to sleep. Easy fatigueability and exercise intolerance are also common complaints related to respiratory compromise.

Compromise of left ventricular forward function may result in symptoms of poor systemic circulation such as dizziness, confusion and cool extremities at rest.

[edit] Right-sided failure

Backward failure of the right ventricle leads to congestion of systemic capillaries. This helps to generate excess fluid accumulation in the body. This causes swelling under the skin (termed peripheral edema or anasarca) and usually affects the dependent parts of the body first (causing foot and ankle swelling in people who are standing up, and sacral edema in people who are predominantly lying down). Nocturia (frequent nighttime urination) may occur when fluid from the legs is returned to the bloodstream while lying down at night. In progressively severe cases, ascites (fluid accumulation in the abdominal cavity causing swelling) and hepatomegaly (painful enlargement of the liver) may develop. Significant liver congestion may result in impaired liver function, and jaundice and even coagulopathy (problems of decreased blood clotting) may occur.

[edit] Signs

[edit] Left-sided failure

Common respiratory signs are tachypnea (increased rate of breathing) and increased work of breathing (non-specific signs of respiratory distress). Rales or crackles, heard initially in the lung bases, and when severe, throughout the lung fields suggest the development of pulmonary edema (fluid in the alveoli). Dullness of the lung fields to finger percussion and reduced breath sounds at the bases of the lung may suggest the development of a pleural effusion (fluid collection in between the lung and the chest wall). Cyanosis which suggests severe hypoxemia, is a late sign of extremely severe pulmonary edema.

Additional signs indicating left ventricular failure include a laterally displaced apex beat (which occurs if the heart is enlarged) and a gallop rhythm (additional heart sounds) may be heard as a marker of increased blood flow, or increased intra-cardiac pressure. Heart murmurs may indicate the presence of valvular heart disease, either as a cause (e.g. aortic stenosis) or as a result (e.g. mitral regurgitation) of the heart failure.

[edit] Right-sided failure

Physical examination can reveal pitting peripheral edema, ascites, and hepatomegaly. Jugular venous pressure is frequently assessed as a marker of fluid status, which can be accentuated by the hepatojugular reflux. If the right ventriclar pressure is increased, a parasternal heave may be present, signifying the compensatory increase in contraction strength.

[edit] Causes

[edit] Chronic Heart Failure

The predominance of causes of heart failure are difficult to analyse due to challenges in diagnosis, differences in populations, and changing prevalence of causes with age.

A 19 year study of 13000 healthy adults in the United States (the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES I) found the following causes ranked by Population Attributable Risk score: [18]

- Ischaemic Heart Disease 62%

- Cigarette Smoking 16%

- Hypertension (high blood pressure)10%

- Obesity 8%

- Diabetes 3%

- Valvular Heart Disease 2% (much higher in older populations)

An Italian registry of over 6200 patients with heart failure showed the following underlying causes: [19]

- Ischaemic Heart Disease 40%

- Dilated Cardiomyopathy 32%

- Valvular Heart Disease 12%

- Hypertension 11%

- Other 5%

Rarer causes of heart failure include:

- Viral Myocarditis (an infection of the heart muscle)

- Infiltrations of the muscle such as amyloidosis

- HIV cardiomyopathy (caused by Human Immunodeficiency Virus)

- Connective Tissue Diseases such as Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Abuse of drugs such as alcohol

- Pharmaceutical drugs such as chemotherapeutic agents.

- Arrhythmias

Obstructive Sleep Apnea a condition of sleep disordered breathing overlaps with obesity, hypertension and diabetes and is regarded as an independent cause of heart failure.

[edit] Acute decompensated heart failure

- See main article: Acute decompensated heart failure

Chronic stable heart failure may easily decompensate. This most commonly results from an intercurrent illness (such as pneumonia), myocardial infarction (a heart attack), arrhythmias, uncontrolled hypertension, or a patient's failure to maintain a fluid restriction, diet or medication.[20] Other well recognised precipitating factors include anaemia and hyperthyroidism which place additional strain on the heart muscle. Excessive fluid or salt intake, and medication that causes fluid retention such as NSAIDs and thiazolidinediones, may also precipitate decompensation.

Pathophysiology

Heart failure is caused by any condition which reduces the efficiency of the myocardium, or heart muscle, through damage or overloading. As such, it can be caused by as diverse an array of conditions as myocardial infarction (in which the heart muscle is starved of oxygen and dies), hypertension (which increases the force of contraction needed to pump blood) and amyloidosis (in which protein is deposited in the heart muscle, causing it to stiffen). Over time these increases in workload will produce changes to the heart itself:

- Reduced contractility, or force of contraction, due to overloading of the ventricle. In health, increased filling of the ventricle results in increased contractility (by the Frank-Starling law of the heart) and thus a rise in cardiac output. In heart failure this mechanism fails, as the ventricle is loaded with blood to the point where heart muscle contraction becomes less efficient. This is due to reduced ability to cross-link actin and myosin filaments in over-stretched heart muscle.[22]

- A reduced stroke volume, as a result of a failure of systole, diastole or both. Increased end systolic volume is usually caused by reduced contractility. Decreased end diastolic volume results from impaired ventricular filling – as occurs when the compliance of the ventricle falls (i.e. when the walls stiffen).

- Reduced spare capacity. As the heart works harder to meet normal metabolic demands, the amount cardiac output can increase in times of increased oxygen demand (e.g. exercise) is reduced. This contributes to the exercise intolerance commonly seen in heart failure.

- Increased heart rate, stimulated by increased sympathetic activity in order to maintain cardiac output. Initially, this helps compensate for heart failure by maintaining blood pressure and perfusion, but places further strain on the myocardium, increasing coronary perfusion requirements, which can lead to worsening of ischemic heart disease. Sympathetic activity may also cause potentially fatal arrhythmias.

- Hypertrophy (an increase in physical size) of the myocardium, caused by the terminally differentiated heart muscle fibres increasing in size in an attempt to improve contractility. This may contribute to the increased stiffness and decreased ability to relax during diastole.

- Enlargement of the ventricles, contributing to the enlargement and spherical shape of the failing heart. The increase in ventricular volume also causes a reduction in stroke volume due to mechanical and contractile inefficiency.[23]

The general effect is one of reduced cardiac output and increased strain on the heart. This increases the risk of cardiac arrest (specifically due to ventricular dysrhythmias), and reduces blood supply to the rest of the body. In chronic disease the reduced cardiac output causes a number of changes in the rest of the body, some of which are physiological compensations, some of which are part of the disease process:

- Arterial blood pressure falls. This destimulates baroreceptors in the carotid body and aortic arch which link to the nucleus tractus solitarius. This center in the brain increases sympathetic activity, releasing catecholamines into the blood stream. Binding to alpha-1 receptors results in systemic arterial vasoconstriction. This helps restore blood pressure but also increases the total peripheral resistance, increasing the workload of the heart. Binding to beta-1 receptors in the myocardium increases the heart rate and make contractions more forceful, in an attempt to increase cardiac output. This also, however, increases the amount of work the heart has to perform.

- Increased sympathetic stimulation also causes the hypothalamus to secrete vasopressin (also known as antidiuretic hormone or ADH), which causes fluid retention at the kidneys. This increases the blood volume and blood pressure.

- Reduced perfusion (blood flow) to the kidneys stimulates the release of renin – an enzyme which catalyses the production of the potent vasopressor angiotensin. Angiotensin and its metabolites cause further vasocontriction, and stimulate increased secretion of the steroid aldosterone from the adrenal glands. This promotes salt and fluid retention at the kidneys, also increasing the blood volume.

- The chronically high levels of circulating neuroendocrine hormones such as catecholamines, renin, angiotensin, and aldosterone affects the myocardium directly, causing structural remodelling of the heart over the long term. Many of these remodelling effects seem to be mediated by transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta), which is a common downstream target of the signal transduction cascade initiated by catecholamines[24] and angiotensin II[25], and also by epidermal growth factor (EGF), which is a target of the signaling pathway activated by aldosterone[26]

- Reduced perfusion of skeletal muscle causes atrophy of the muscle fibres. This can result in weakness, increased fatigueability and decreased peak strength - all contributing to exercise intolerance.[27]

The increased peripheral resistance and greater blood volume place further strain on the heart and accelerates the process of damage to the myocardium. Vasoconstriction and fluid retention produce an increased hydrostatic pressure in the capillaries. This shifts of the balance of forces in favour of interstitial fluid formation as the increased pressure forces additional fluid out of the blood, into the tissue. This results in edema (fluid build-up) in the tissues. In right-sided heart failure this commonly starts in the ankles where venous pressure is high due to the effects of gravity (although if the patient is bed-ridden, fluid accumulation may begin in the sacral region.) It may also occur in the abdominal cavity, where the fluid build-up is called ascites. In left-sided heart failure edema can occur in the lungs - this is called cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. This reduces spare capacity for ventilation, causes stiffening of the lungs and reduces the efficiency of gas exchange by increasing the distance between the air and the blood. The consequences of this are shortness of breath, orthopnoea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea.

The symptoms of heart failure are largely determined by which side of the heart fails. The left side pumps blood into the systemic circulation, whilst the right side pumps blood into the pulmonary circulation. Whilst left-sided heart failure will reduce cardiac output to the systemic circulation, the initial symptoms often manifest due to effects on the pulmonary circulation. In systolic dysfunction, the ejection fraction is decreased, leaving an abnormally elevated volume of blood in the left ventricle. In diastolic dysfunction, end-diastolic ventricular pressure will be high. This increase in volume or pressure backs up to the left atrium and then to the pulmonary veins. Increased volume or pressure in the pulmonary veins impairs the normal drainage of the alveoli and favors the flow of fluid from the capillaries to the lung parenchyma, causing pulmonary edema. This impairs gas exchange. Thus, left-sided heart failure often presents with respiratory symptoms: shortness of breath, orthopnea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea.

In severe cardiomyopathy, the effects of decreased cardiac output and poor perfusion become more apparent, and patients will manifest with cold and clammy extremities, cyanosis, claudication, generalized weakness, dizziness, and syncope

The resultant hypoxia caused by pulmonary edema causes vasoconstriction in the pulmonary circulation, which results in pulmonary hypertension. Since the right ventricle generates far lower pressures than the left ventricle (approximately 20 mmHg versus around 120 mmHg, respectively, in the healthy individual) but nonetheless generates cardiac output exactly equal to the left ventricle, this means that a small increase in pulmonary vascular resistance causes a large increase in amount of work the right ventricle must perform. However, the main mechanism by which left-sided heart failure causes right-sided heart failure is actually not well understood. Some theories invoke mechanisms that are mediated by neurohormonal activation. Mechanical effects may also contribute. As the left ventricle distends, the intraventricular septum bows into the right ventricle, decreasing the capacity of the right ventricle.

[edit] Systolic dysfunction

Heart failure caused by systolic dysfunction is more readily recognized. It can be simplistically described as failure of the pump function of the heart. It is characterized by a decreased ejection fraction (less than 45%). The strength of ventricular contraction is attenuated and inadequate for creating an adequate stroke volume, resulting in inadequate cardiac output. In general, this is caused by dysfunction or destruction of cardiac myocytes or their molecular components. In congenital diseases such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy, the molecular structure of individual myocytes is affected. Myocytes and their components can be damaged by inflammation (such as in myocarditis) or by infiltration (such as in amyloidosis). Toxins and pharmacological agents (such as ethanol, cocaine, and amphetamines) cause intracellular damage and oxidative stress. The most common mechanism of damage is ischemia causing infarction and scar formation. After myocardial infarction, dead myocytes are replaced by scar tissue, deleteriously affecting the function of the myocardium. On echocardiogram, this is manifest by abnormal or absent wall motion.

Because the ventricle is inadequately emptied, ventricular end-diastolic pressure and volumes increase. This is transmitted to the atrium. On the left side of the heart, the increased pressure is transmitted to the pulmonary vasculature, and the resultant hydrostatic pressure favors extravassation of fluid into the lung parenchyma, causing pulmonary edema. On the right side of the heart, the increased pressure is transmitted to the systemic venous circulation and systemic capillary beds, favoring extravassation of fluid into the tissues of target organs and extremities, resulting in dependent peripheral edema.

[edit] Diastolic dysfunction

Heart failure caused by diastolic dysfunction is generally described as the failure of the ventricle to adequately relax and typically denotes a stiffer ventricular wall. This causes inadequate filling of the ventricle, and therefore results in an inadequate stroke volume. The failure of ventricular relaxation also results in elevated end-diastolic pressures, and the end result is identical to the case of systolic dysfunction (pulmonary edema in left heart failure, peripheral edema in right heart failure.)

Diastolic dysfunction can be caused by processes similar to those that cause systolic dysfunction, particularly causes that affect cardiac remodeling.

Diastolic dysfunction may not manifest itself except in physiologic extremes if systolic function is preserved. The patient may be completely asymptomatic at rest. However, they are exquisitely sensitive to increases in heart rate, and sudden bouts of tachycardia (which can be caused simply by physiological responses to exertion, fever, or dehydration, or by pathological tachyarrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response) may result in flash pulmonary edema. Adequate rate control (usually with a pharmacological agent that slows down AV conduction such as a calcium channel blocker or a beta-blocker) is therefore key to preventing decompensation.

Left ventricular diastolic function can be determined through echocardiography by measurement of various parameters such as the E/A ratio (early-to-atrial left ventricular filling ratio), the E (early left ventricular filling) deceleration time, and the isovolumic relaxation time.

[edit] Diagnosis

Chest x-ray showing an enlarged cardiac silhouette due to congestive heart failure.

[edit] Imaging

Echocardiography is commonly used to support a clinical diagnosis of heart failure. This modality uses ultrasound to determine the stroke volume (SV, the amount of blood in the heart that exits the ventricles with each beat), the end-diastolic volume (EDV, the total amount of blood at the end of diastole), and the SV in proportion to the EDV, a value known as the ejection fraction. In pediatrics, the shortening fraction is the preferred measure of systolic function. Normally, the EF should be between 50% and 70%; in systolic heart failure, it drops below 40%. Echocardiography can also identify valvular heart disease and assess the state of the pericardium (the connective tissue sac surrounding the heart). Echocardiography may also aid in deciding what treatments will help the patient, such as medication, insertion of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator or cardiac resynchronization therapy. Echocardiography can also help determine if acute myocardial ischemia is the precipitating cause, and may manifest as regional wall motion abnormalities on echo.

Chest X-rays are frequently used to aid in the diagnosis of CHF. In the compensated patient, this may show cardiomegaly (visible enlargement of the heart), quantified as the cardiothoracic ratio (proportion of the heart size to the chest). In left ventricular failure, there may be evidence of vascular redistribution ("upper lobe blood diversion" or "cephalization"), Kerley lines, cuffing of the areas around the bronchi, and interstitial edema.

[edit] Electrophysiology

An electrocardiogram (ECG/EKG) is used to identify arrhythmias, ischemic heart disease, right and left ventricular hypertrophy, and presence of conduction delay or abnormalities (e.g. left bundle branch block). An ECG may also diagnose acute myocardial ischemia or infarction (if ST depression or elevation are present).

[edit] Blood tests

Blood tests routinely performed include electrolytes (sodium, potassium), measures of renal function, liver function tests, thyroid function tests, a complete blood count, and often C-reactive protein if infection is suspected. An elevated B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) is a specific test indicative of heart failure. Additionally, BNP can be used to differentiate between causes of dyspnea due to heart failure from other causes of dyspnea. If myocardial infarction is suspected, various cardiac markers may be used.

According to a meta-analysis comparing BNP and N-terminal pro-BNP (NTproBNP) in the diagnosis of heart failure, BNP is a better indicator for heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction. In groups of symptomatic patients, a diagnostic odds ratio of 27 for BNP compares with a sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 84% in detecting heart failure. [28]

[edit] Angiography

Heart failure may be the result of coronary artery disease, and its prognosis depends in part on the ability of the coronary arteries to supply blood to the myocardium (heart muscle). As a result, coronary catheterization may be used to identify possibilities for revascularisation through percutaneous coronary intervention or bypass surgery.

[edit] Monitoring

Various measures are often used to assess the progress of patients being treated for heart failure. These include fluid balance (calculation of fluid intake and excretion), monitoring body weight (which in the shorter term reflects fluid shifts).